Imagine a world where pregnant women brandish swords and don martial helmets, while fetuses are envisioned as future avengers of their slain fathers. This is the harsh reality depicted in the groundbreaking interdisciplinary study that focuses on pregnancy during the Viking Age, authored by myself, Kate Olley, along with Brad Marshall and Emma Tollefsen as part of the Body-Politics project. Despite being a central aspect of the human experience, pregnancy has often been neglected in archaeological research, primarily due to its minimal material evidence.

In particular, the subject of pregnancy has been largely overlooked in historical contexts predominantly associated with warriors, kings, and battles—like the romanticized Viking Age (circa AD 800 to AD 1050). Traditional narratives often classify topics like childbirth as mere “women’s issues,” relegated to the so-called “natural” or “private” realms. However, we argue that profound questions such as “when does life begin?” transcend private matters and are indeed of significant political importance, resonating just as strongly today as they did in the past.

In our comprehensive study, my co-authors and I gathered diverse strands of evidence to unravel how pregnancy and the pregnant body were perceived during this period. By delving into what we term “womb politics,” we aim to enhance our understanding of gender, body politics, and the intricacies of sexual politics in the Viking Age and beyond.

Our initial approach involved analyzing terms and narratives surrounding pregnancy in Old Norse literature. Though these texts were produced in the centuries following the Viking Age, sagas and legal documents provide rich linguistic and narrative insights that were disseminated among the Vikings’ direct descendants. Through this analysis, we discovered that pregnancy could be articulated in various terms such as “bellyful,” “unlight,” and “not whole.” Additionally, we noted an intriguing belief in the potential personhood of a fetus, encapsulated in the phrase: “A woman walking not alone.”

Wiki Commons

One saga episode we examined supports the notion that unborn children, particularly those of high status, were already woven into complex networks of kinship, alliances, feuds, and obligations. This narrative recounts a tense encounter involving the pregnant Guðrún Ósvífrsdóttir, a central character in the Saga of the People of Laxardal, and her husband’s murderer, Helgi Harðbeinsson. In a provocative act, Helgi wipes his bloodied spear on Guðrún’s clothing and over her abdomen, ominously proclaiming: “I think that under the corner of that shawl dwells my own death.” This grim prophecy indeed comes to fruition, as the fetus grows up to avenge its father’s death.

Another compelling episode, taken from the Saga of Erik the Red, highlights the agency of the mother in a perilous situation. The heavily pregnant Freydís Eiríksdóttir finds herself embroiled in an attack by the skrælings, the term used by the Norse to describe the indigenous populations of Greenland and Canada. When escape becomes impossible due to her pregnancy, Freydís bravely grabs a sword, exposes her breast, and strikes the sword against it, effectively intimidating her attackers into retreat.

Although this tale is sometimes dismissed as trivial in academic circles, it resonates with another remarkable piece of evidence we investigated for our study: a figurine depicting a pregnant woman.

This pendant, discovered in a tenth-century woman’s grave in Aska, Sweden, represents the only credible representation of pregnancy from the Viking Age. The figurine portrays a woman in traditional female attire, her arms cradling a pronounced belly—suggesting a deep connection to the unborn child. What makes this particular figurine especially intriguing is that the pregnant figure is adorned with a martial helmet.

Historiska Museet, CC BY-ND

Collectively, these diverse pieces of evidence suggest that pregnant women were, at least in artistic representations and narratives, involved in violence and wielding weapons. They were not merely passive figures. Coupled with recent investigations into Viking women interred as warriors, this revelation prompts a reevaluation of our understanding of gender roles in societies typically perceived as hyper-masculine.

Understanding the Loss of Infants and the Perception of Pregnancy as a Defect

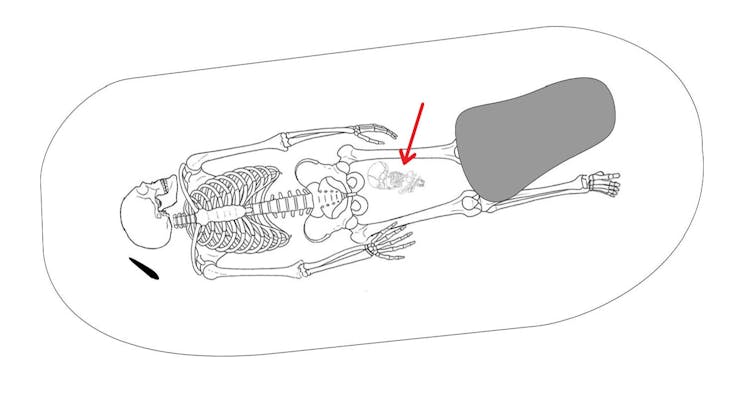

Another vital aspect of our investigation focused on identifying evidence of obstetric deaths within the Viking burial records. It is widely believed that maternal and infant mortality rates were alarmingly high in most pre-industrial societies. However, our research revealed that out of thousands of Viking graves, only 14 possible mother-infant burials were documented.

As a result, we propose that pregnant women who died were not typically buried alongside their unborn children and may not have been memorialized as a singular, symbiotic entity by Viking societies. Furthermore, our findings indicated that newborns were sometimes interred with adult males and post-menopausal females, suggesting these assemblages could represent family graves, or perhaps something entirely different.

Matt Hitchcock / Body-Politics, CC BY-SA

It remains possible that infants—who are generally underrepresented in burial records—were disposed of in alternative locations post-mortem. When discovered in graves alongside other bodies, it’s plausible that they were included as grave goods, objects intended to accompany the deceased in their eternal rest.

This situation starkly highlights the vulnerability of both pregnancy and infancy as transitional states within society. One striking piece of evidence encapsulates this reality more than any other. For some, such as Guðrún’s son, gestation and birth represented a complex, multi-staged journey toward becoming a recognized social person.

Conversely, for individuals situated lower on the social hierarchy, the situation may have been vastly different. One of the legal texts we examined states bluntly that when enslaved women were sold, being pregnant was deemed a defect of their bodies. This perspective starkly contrasts with the more privileged narratives surrounding pregnancy.

In essence, pregnancy was deeply political and held varying meanings for different communities during the Viking Age. It influenced and was influenced by concepts of social standing, kinship, and personhood. Our study demonstrates that pregnancy was not a hidden or private matter; rather, it played a crucial role in shaping how Viking societies understood life, social identities, and power dynamics.

Marianne Hem Eriksen is an associate professor of archaeology at the University of Leicester. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

![]()